Spacing Effect and Vocabulary Learning

In the previous post, I talked about the importance of repetition for learning new vocabulary. Some interesting research on repetition has provided some answers on the questions of when and how often to review vocabulary words.

Back when I began learning Korean, I tried to learn 10 or so words per day by writing them down in a small notebook along with the English translations. While riding the subway to and from work, I would take out the notebook and quiz myself. I knew that I needed to review the words I had studied, but I wasn’t sure how to do it. Do I review ALL the words each day? As the list grew to hundreds of words, this soon became impractical. I tried a variety of plans and finally settled on reviewing the most recent 20 or so words I was studying, and then periodically (i.e., whenever the mood struck me) recheck my earliest pages.

Though my reviews of most recent 20 words went well enough, my reviews of the earliest pages did not go so well. I realized I was forgetting more than half of them, and I feared that despite my additional reviews, the words would slip away later as well. There were also times when I was speaking in Korean and was unable to recall a word that I knew I had ‘learned’ from my vocabulary study. It seemed hopeless, and I soon lost my motivation for further vocabulary study. At that time, I probably already had the 2000 or so most common Korean words, and this was enough to ‘get by’ in the language. However, I wanted to do more than just get by, and my lack of an advanced vocabulary seemed to be an insurmountable barrier.

Probably not the title of a future best-selling motivational book

What is the spacing effect?

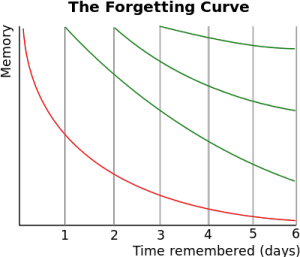

What I would have benefited from then is an awareness of the spacing effect. Again, we go all the way back to Hermann Ebbinghaus, who is considered the originator of the theory. Ebbinghaus found that he was able retain information longer when his review sessions were spaced over a matter of days or weeks (‘spaced repetition’) as compared to when the review sessions were done within one lengthy but uninterrupted session ( ‘massed repetition’).

If you’ve read the previous article, this is your second review of Ebbinghaus’s picture. Review it again in 3 weeks, and then again in 3 months, and you’ll remember that beard for the rest of your life.

Here’s a fairly straightforward example of what is meant by ‘spaced’ versus ‘massed’ repetition for learning. Let’s say you want your students to learn 30 new vocabulary words. One option is set aside 30 minutes of one class to have students study and practice the words. As all this is done within one 30-minute block of time with no breaks, we call this massed repetition.

The other option is to divide the same 30 minutes worth of study and practice into three 10-minute lessons spaced out over several days (e.g., 10 minutes on Wednesday, 10 minutes on Thursday, and the final 10 minutes on Friday). While the total time for study is the same as the massed repetition option, the instruction is spaced out over three days, and is thus called ‘spaced repetition.’

Research has found that students learning material through spaced repetition are able to retain what they learned far longer than material learned through massed repetition. The example I gave above was taken from a study by Bloom and Shuell( 1981) involving English speakers learning French vocabulary. Right after the final study session for each group, the researchers gave a post-test and found that both groups made roughly identical gains (cramming, as it turns out, does very well for short-term learning). However, four days later the researchers gave a surprise second test and found that the spaced repetition group retained nearly all their gains (only declining 1.84 on average on the 20-point test), while the massed repetition group suffered a decline of nearly 5 points. Basically, spacing out study sessions allows us to hold on to what we learn longer.

This is the first picture that appeared on an image search for Bloom and Shuell, so I went with it.

(third scholar in the picture not identified).

The work of Ebbinghaus has been validated by a number of researchers and found to be particularly robust, extending to just about every learning domain investigated, including math, memorizing science facts, and remembering pictures. Not only is the spacing effect well established, but the sheer size of effect dwarfs most other findings in the psychology literature(Dempster, 1996). Whereas many studies showing significant effects of various teaching practices have moderate to small effect sizes, studies on the spacing effect often generally show gains of twice the size of results gained from massed presentation. Memory researchers Bahrick and Hall(2005) state, “The spacing effect is one of the oldest and best documented phenomena in the history of learning and memory research.”

May have been a bit more successful in my image search for Lynda Hall and Harry Bahrick.

When to review?

So the big question as to how to help our students take advantage of the spacing effect is the exact timing of the reviews. Research on the spacing effect has investigated a wide range of spacing schedules, ranging from a matter of seconds to as many as 60 days between study sessions. There seems to be little consensus on an ideal repetition schedule, but there are some guidelines for efficient and practical spacing schedules.

Researchers Landauer and Bjork(1978) found two seemingly contradictory aspects of the spacing effect. Generally, longer intervals between study sessions were more effective than shorter ones. Waiting one week between review sessions, for example, provided better retention than waiting one day between sessions. However, if the intervals were spaced too far apart, the benefits of the spacing effect quickly faded away.

No pictures of Landauer and Bjork available, but here’s a different Bjork reminding us that there are alternatives to the spacing effect to making something stick in long-term memory

A good analogy to make sense of what is happening here is weight lifting or endurance training. After a good workout, muscles are torn down and need time to repair themselves and grow stronger. Longer resting periods are more helpful than shorter resting periods: resting for 4 hours is much better than 2 hours, waiting 24 hours is better than 12 hours, and so on. However, what happens if you wait too long before hitting the gym again? At some point the muscles will no longer benefit from rest and will begin to atrophy, returning to the same strength as before you had your workout. If this is allowed to happen, the initial workout session becomes meaningless.

The same phenomenon seems to apply for memories: after learning something, some wait time is helpful and perhaps even crucial, but if you wait too long, you’ll lose everything.

Landauer and Bjork(1978) thus propose the following considerations:

1) Generally, retrieval spacings should be far apart.

2) Rehearsals are only effective if retrieval is successful (thus, not spaced too far apart).

3) Successful retrieval strengthens the memory, allowing for further successful retrieval at increasingly lengthy intervals.

These considerations suggest a repetition schedule based on expanding intervals¹. At first, repetition sessions should be somewhat close together, as much of what we learn is forgotten quickly, but with each repetition the time before the following review sessions can be scheduled increasingly further apart.

In terms of possible repetition schedule options, language scholar Paul Pimsleur(1967) proposed an expanding schedule of 5 seconds, 25 seconds, 2 minutes, 10 minutes, 1 hour, 5 hours, 1 day, 5 days, 25 days and 4 months. This is useful, but not particularly practical in the initial stages (imagine trying to time out 5, 25 and 120 seconds for every word studied).

Yes, that’s Paul Pimsleur’s image on an advertisement for the language learning program that proudly exploits bears his name. I’m sure he gave his enthusiastic approval to the marketing team for this ad in a business meeting conducted via Skype (Ouija board plugin–Pimsleur passed away in 1976). For any language professors reading this that didn’t get the memo to hate that ol’ devil Paul, consider yourselves informed.

A more practical repetition schedule could do away with the review sessions between 5 seconds and 5 hours and just have the second review 24 hours after the initial study time. The following reviews can come a week, a month, and then 3 (or 4) months later.

- Initial learning

- 1-day review

- 1-week review

- 1-month review

- 3-month review

This might require a lengthier review sessions at the 1-day and 1-week review periods, but the schedule is practical and easy to remember. For Praxis, we generally follow this model and include an additional 2-year review for our long-term users.

Perhaps the biggest benefit of online vocabulary programs is that the system can take care of the task of remembering which words are up for a review. In most programs, including Praxis, the student simply logs on and the program introduces new words along with words that are due for review.

A number of SLA scholars have talked about the spacing effect for vocabulary learning (Nation, 2001, Schmidt, 2000; Takac, 2008; Thornbury, 2002). There are a few scholars (Bird, 2010; Year, 2009, and yours truly included) who have investigated applying the spacing effect to grammar instruction with positive results. In the future I’ll probably post more on the spacing effect, including some of our own research on the subject.

The most common image search result for ‘Scott Miles’.

Here comes the smolder…

- This is not to say that expanding repetition schedule is the only way to go. A number of researchers (Cepeda et al., 2008; Mozer et al., 2009; Rohrer & Pashler, 2007; Bird, 2010) have explored uniform intervals (e.g., review sessions every two weeks) with considerable success. From my reading of the research, uniform intervals have some advantages, but for practical classroom applications in the classroom I’ve found that expanding repetition schedules work best.

References

Bahrick, H.P., & Hall, L. (2005). The importance of retrieval failures to long-term retention: A metacognitive explanation of the spacing effect. Journal of Memory and Language, 52(4), 566-577.

Bird, S. (2010). Effects of distributed practice on the acquisition of L2 English syntax. Applied Psycholinguistics, 31(4), 635-650.

Bloom, K. F., & Shuell, T. J. (1981). Effects of massed and distributed practice on the learning and retention of second-language vocabulary. Journal of Educational Research, 74, 245–248.

Cepeda, N. J., Vul, E., Rohrer, D., Wixted, J., & Pashler, H. (2008). Spacing effects in learning: A temporal ridgeline of optimal retention Psychological Science,19(11), 1095-1102.

Dempster, F.N. (1996). Distributing and managing the conditions of encoding practice. In E.L. Bjork and R.A. Bjork (Eds.), Memory (pp. 318-339). London: Academic Press.

Donovan, J., & Radosevich, D. (1999). A meta-analytic review of the distribution of practice effect: Now you see it, now you don’t. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84, 795-805.

Landauer, T. K., & Bjork, R. A. (1978). Optimum rehearsal patterns and name learning. In M. M. Gruneberg, P. E. Morris, & R. N. Sykes (Eds.), Practical aspects of memory (pp. 625–632). New York: Academic Press.

Spaced vs. massed distribution instruction for L2 grammar learning, System, 42, 412-428.

Miles, S., & Kwon, C.J. (2008). Benefits of using CALL vocabulary programs to provide systematic word recycling. English Teaching, 63(1), 199-216.

Mozer, M. C., Pashler, H., Cepeda, N., Lindsey, R., & Vul, E. (2009). Predicting the optimal spacing of study: A multiscale context model of memory. In Y. Bengio, D. Schuurmans, J. Lafferty, C. K. I. Williams, & A. Culotta (Eds.), Advances in neural information processing systems 22 (pp. 1321-1329). La Jolla, CA: NIPS Foundation.

Nation, I.S.P. (2001). Learning vocabulary in another language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pimsleur, P. (1967). A memory schedule. Modern Language Journal, 51(2), 73-75.

Rohrer, D., & Pashler, H. (2007). Increasing retention without increasing study time. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(4), 183-186.

Schmidt, N. (2000). Vocabulary in language teaching. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Takac, V. P. (2008). Vocabulary learning strategies and foreign language acquisition. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Thornbury, S. (2002). How to teach vocabulary. Harlow: Longman.

Year, J. (2009). Korean speakers’ acquisition of the English ditransitive construction: The role of input frequency and distribution. Unpublished dissertation. Teacher’s College, Columbia University.