Kumar Snehansu

About 10-15 years ago, my take on technology in the ESL/EFL classroom was that it is certainly helpful for the right kind of teacher, students, and classroom objectives, but it was largely still just an option that could be bypassed without any particular detrimental effect. MOODLE is a good example of this. MOODLE and sites like it were (and are) very helpful for teachers to organize the class, provide materials, collect assignments, and so on. However, I wouldn’t have said that a teacher utilizing MOODLE would necessarily provide superior learning outcomes for students than a colleague who went with more old school methods. Technology provided some convenience and more options for the teacher and students, and this in-itself made it worthwhile, but it would not necessarily affect the educational bottom line.

Now I’m not so sure. Learning technology has made great improvements over the last decade to the point where a teacher making smart use of technology may indeed provide better learning outcomes in at least some language skills than the teacher who eschews technology.

Don’t get me wrong. Technology alone won’t do much for a poor teacher who is unable to engage the students on a personal level. An engaging and inspirational teacher is always preferable over those who lack the crucial interpersonal skills and knowledge needed to make learning happen in the classroom. However, what I am coming to believe is that given two teachers of generally equal teaching skill, the teacher who utilizes technology more effectively will get better learning outcomes.

Of course, the big caveat here is that teachers use technology effectively. Many may not. Using technology just for its own sake can easily be counter-productive (here’s a helpful article on the effective use of educational technology). My central argument is that any technology that gives students access to more quality practice and individualized feedback than what can practically be provided in the traditional classroom setting alone should result in better learning.

The following are some specific areas in which I believe technology can have a strong impact on learning.

Vocabulary Programs

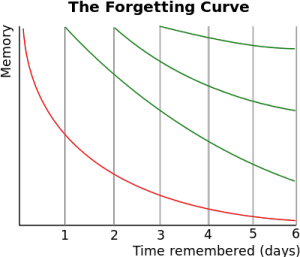

It’s no surprise that in my admittedly biased view this would top my list. I think it’s hard to make an argument against using a vocabulary program that provides spaced repetition of vocabulary to ensure retention and allows tailored instruction to match the students level. Further, these programs allow the teacher more time in class to engage students in communicative activities. If you need more details on these arguments, read just about every other post on this blog. 🙂

Grammar

Grammar is another area where a good program can give more opportunities for practice and individualized feedback. Currently I teach an advanced grammar course using the Azar grammar course book. For the first semester I used the accompanying workbook and was not happy with the results. There was no way for me to know if my students just checked the answer key in the back of the workbook rather than sincerely tried to do the exercises. A colleague and I decided to make our own online workbook that covered the concepts taught from the main course book using the Canvas Network that my university provides. I’ve seen an improvement on test scores that I suspect is due to these online practices more than anything else. For one thing, it is more difficult for the student to get the answers without actually doing the work. Secondly, students can retake the quizzes repeatedly until they get 100%, rather than just submit the workbook and get one score, and the quizzes draw on question banks so not every quiz is identical. Finally, I can see the exact test results, find out where students are having trouble, and then give additional instruction (in class or individually with the student). My students are getting far more additional practice than with the paper workbook, and I’m in a position to better address problematic areas.

Much more than this can be done, however, and this is an area that is ripe for further innovation. I would love to see spacing effect methodology applied to explicit grammar study and practice, for example. Praxis has done a little work with this, but we haven’t had the chance as of yet to fully implement some of our ideas.

Reading and Listening

Technology can give students access to a lot more practice in reading and listening than is available through standard classroom materials. Through our public school system here in the States, my children have access to a website that has a full line of graded reading materials that students can read on their own outside of class. This is a lot easier to manage than trying to track down books at my children’s level at the library. For instructors doing extensive reading with their students (as well they should), sites like M-reader and X-reading help teachers monitor student progress. English Central is a site that provides interesting listening materials at different levels, along with a good learner management system for teachers. Students primarily get better at listening and reading by extensive practice. The best listening and reading strategy instruction cannot replace the 1000s of hours on task that is needed for true improvement. A teacher sticking solely with the traditional coursebook simply can’t provide students with the amount of practice students need to make substantial progress. Technology makes this easier to do.

Writing

The vast majority of writing in the world outside the classroom is done on computers. Students need to become comfortable typing English on keyboards and increasingly on mobile devices. Ample practice on these mediums is crucial. I’ve encountered many students who prefer to write by hand because they aren’t fast enough on the keyboard. Writing by hand is fine, but it doesn’t get you very far in the workplace, and the speed of writing by hand simply cannot compete with typing by keyboard. These are crucial skills a good writing class should develop, with typing speed being at least a secondary objective of the course.

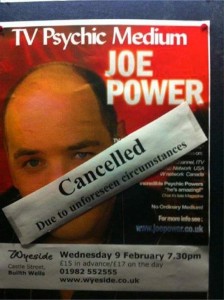

Yeah, but more time in class for writing on keyboards might cut into their chiseling practice!

Students should also know how to use spell and grammar checks effectively. They certainly do not replace the need for students to improve their spelling and grammar, but these programs are tools that students will need (just as native speakers do) when they move on from our ESL/EFL classes.

Speaking

There are some programs available now that allow students to make recordings of themselves speaking on a topic. These not only give students a chance to increase their fluency by speaking more outside the classroom (in a way that the teacher can check to make sure they have really done it!), but students can also hear how they sound. This is crucial for pronunciation development. The way we think we sound in a new language can be shockingly different than what others are hearing when we speak.

What do you mean my mask makes me sound like Mufasa?

Technology that gives students access to more practice and individualized feedback than what can be provided in the classroom alone should have a strong impact on learning outcomes. A teacher without these resources would be hard-pressed to match them.

So what does this mean? Should teachers who refuse to take advantage of technology be shown the door? Again, I wouldn’t go this far. Teachers who engage and inspire students are still valuable for a school regardless of the exact methods they use. But at the same time, at what point can we say a teacher is still “good” if he or she purposely avoids tools that are shown to be highly effective for students?

In the meantime, I look forward to the counterpoint article by Clifford Stoll (assuming, of course, this fad known as the Internet is still around).