A language learner needs thousands of words just to reach an intermediate level of proficiency, and as many as 9000 words to have reliable access to reading and listening materials made for native speakers (Nation, 2006). This is no small task, made much harder by the fact that most language learners struggle to remember the vocabulary that they study.

This was certainly my experience when I first started studying Korean. I still have some of my pocket notebooks with lists of Korean words written on one side of the page and the English translations on the other. I added about 10 words every day and studied my rapidly expanding list of words while riding the subway to and from work. The number of pages grew quickly, which gave the impression that I was making progress. However, almost every time I went back to the earlier pages of my notebook to review words, I struggled to recall even a quarter of them. It was a frustrating process of spending so much time studying thousands of words while realizing that the majority of them just weren’t sticking.

Like sands through the sieve, so were the words of my study

I eventually just quit and relied on reading and listening to keep building up my vocabulary. Reading and listening are certainly essential parts of a good vocabulary study program, but I always suspected that input alone was not the fastest way to get the vocabulary that I sorely needed. Explicit study of vocabulary can work, but I just wasn’t doing it the right way.

Why did I forget so much of what I had tried to memorize? One of the main reasons was my failure to review the words properly. Hermann Ebbinghaus, a meticulous German researcher in the late 19th century, established that after learning something most forgetting happens very quickly, with more than half of the content learned being lost within hours after initial study or exposure. He detailed his experiments, all done on himself, in his most famous publication, Memory: A Contribution to Experimental Psychology.

Tragically less popular was his book on how to grow a properly manly beard.

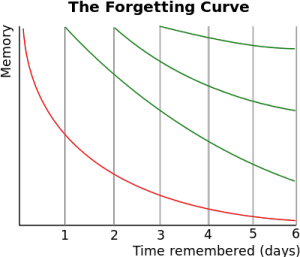

Ebbinghaus presented what has come to be known as the forgetting curve. In the chart below (taken from the Wikipedia entry), the red line represents the rate of forgetting without any repetition. It shows that after a week, very little, if anything, is still retained without any reviews, while the green lines represent how the severity of the forgetting curve is lessened with each repetition.

Ebbinghaus writes,

The series are gradually forgotten, but — as is sufficiently well known — the series which have been learned twice fade away much more slowly than those which have been learned but once. If the re-learning is performed a second, a third or a greater number of times, the series are more deeply engraved and fade out less easily and finally, as one would anticipate, they become possessions of the soul as constantly available as other image-series which may be meaningful and useful.

So repetition is essential to help new vocabulary become ‘possessions of the soul’ (or in far less poetic terminology, move vocabulary knowledge from short to long-term memory). Note that though the forgetting curve shown in the graph implies that content memorized without review would soon be completely forgotten, subsequent research has found that a small but significant percentage will stick even without further review.

Now it is easy for me to see why my initial study of Korean vocabulary was so unproductive. Though I did review words learned from the previous day, weeks and often months had passed before I checked them again, so it is no surprise that I failed to recall even half of what I had been studying. When first studying a word, an engaging vocabulary activity can result in much better retention, of course. Mnemonic techniques such as the keyword method, for example, have good results for helping students remember a new word. However, regardless of the quality of initial study (referred to as ‘initial encoding’ by scholars), a sizable percentage of what is learned will fade without further review.

How many repetitions are needed?

It’s impossible to come up with a specific number on this. A number of factors can have a strong effect on how easy it is to remember a given word. Some words can be learned with only a few reviews; words that are cognates in the learner’s first language might not need any reviews at all. Others are closely related to other English words the student may have already learned (e.g., learning the word elevation after already knowing the word elevator), while other words might lend themselves well to mnemonic aids such as the keyword method. Anyone who has studied a foreign language has had experiences in which one encounter with a new word was enough to retain it, while other words remain elusive even after dozens of encounters. Another major factor is how the timing of reviews can have a big impact on retention. This is known as the ‘spacing effect,’ and I’ll go into this in more detail in the next blog entry.

Nonetheless, research on the subject has given some fairly good guidance as to how many times a student will, in general, need to review a word before it sticks in long-term memory. Ebbinghaus needed six repetitions to memorize lists of ‘nonsense words’ to bring them “to the point of first possible reproduction” (but it took Ebbinghaus only five repetitions to memorize 6 stanzas of Byron’s Don Juan–an interesting but perhaps understandable choice of literature for a researcher who may not have gotten out so much).

Too much ‘spacing effect’ for this to qualify as a beard.

Kachroo (1962) found that words repeated seven times or more in a course book were known by most learners. Crothers and Suppes (1967) also found 6-7 repetitions were enough to help students retain 80% of the 216 Russian-English word pairs studied in their experiment. So to answer the question, 6-7 explicit reviews may be enough for the average word. In conditions where students are learning words through reading, Nation (2014) suggests a minimum of 12 encounters with the word. “Twelve repetitions…are enough to allow the opportunity for several dictionary look-ups, several unassisted retrievals, and an opportunity to meet each word in a wide variety of contexts.”

Speaking of ‘wide variety of contexts’, repetition doesn’t need to be limited to only remembering the meaning of a word, but also can be useful for increasing knowledge about the word, or what is also known as developing ‘depth’ of vocabulary knowledge. How is the word used by native speakers? What other words (collocations) commonly occur with it? How is the word pronounced? Can you recognize the word when you hear it? This is the downside of simple L1-L2 flash card activities that do little, if anything, to improve the depth vocabulary knowledge. I’ll have more on how Praxis deals with this in a future article.

What does this mean for your teaching?

First off, it’s my opinion that teachers should make sure vocabulary growth is a central part of their syllabus, regardless of the particular purpose of their language class. At every level of proficiency, vocabulary tops the expressed needs of students (Folse, 2004). Students know they need more vocabulary and most will appreciate any opportunity given by teachers to expand their vocabulary. However, teachers should keep in mind that without consideration for repetition, students will forget the bulk of what is learned in the class, and just as I experienced when learning Korean, this can be demotivating.

I see three things teachers can do to keep their students building up their vocabulary in a meaningful and lasting way:

- Build vocabulary review lessons into your syllabus

Ebbinghaus concluded his book with the following advice for the teacher:

The school-boy doesn’t force himself to learn his vocabularies and rules altogether at night, but knows that he must impress them again in the morning. A teacher distributes his class lesson not indifferently over the period at his disposal, but reserves in advance a part of it for one or more reviews.

New vocabulary should be reviewed systematically throughout the course. These reviews can (and generally should) be brief. A simple reminder quiz at the beginning of each class can be enough. Don’t be surprised or discouraged if some students get many of the answers wrong, as this is an expected part of the learning process. The act of simply testing and then reviewing the answers is enough to count as a good review session. As we expect some degree of forgetting to occur from test to test, I recommend not grading the quizzes. Simply give the quiz and then check the answers as a class. If the students are attentive and making an effort, learning will happen.

Of course, activities other than quizzes can be useful for reviews. There are a number of quick vocabulary games that will do the trick. Brief reading or listening passages that give further exposure to the vocabulary can be useful (though they take up a bit more time and some target words might be ignored or overlooked by students). Speaking activities likewise could be ideal, should the target vocabulary lend themselves to such.

As noted earlier, the next article will concern the timing of the reviews. For now, I’ll leave you with a schedule that I use with my students and give the rationale in more detail in the next article.

- Initial presentation

- First review in the next class (or as homework)

- Second review roughly 1 week after the initial presentation

- Third review 3-4 weeks after the initial presentation

- Fourth review (if possible) 3-4 months after the initial presentation

As may be readily apparent, words that are introduced later in the semester will not have the option for the fourth (and perhaps even the third) review. Nonetheless, a sizable percentage of the vocabulary introduced in the class will be well on its way to mastery.

- Extensive reading and listening

With enough exposure to English, students can get needed reviews of words naturally through reading and listening extensively. As this is a practice that can extend beyond one semester and delivers benefits beyond vocabulary learning, extensive reading and listening are key to long-term language success. Extensive reading and listening do require a lot of time and motivation on the part of the students, but then again, what complex skill does not? This guide, put out by the Extensive Reading Foundation, can help teachers new to the practice understand exactly what extensive reading is and how it can be introduced into the classroom.

- Use online vocabulary programs

Of course, vocabulary learning websites like Praxis are designed with repetition in mind. These programs generally allow individual students to study vocabulary that matches their levels and needs and provide adaptive feedback (extra practice only where needed). They also have the advantage of giving vocabulary practice outside of the classroom, and thus can free up time for other classroom activities. These programs can also save the teacher a considerable amount of time as they automatically give corrections to the students and allow teachers to monitor student progress easily.

One major factor in making Praxis was to give not only the necessary number of repetitions needed for long-term learning, but also additional information about the word. With each repetition, learners engage the word in a different way. For example, learners might see the word in a new context, have to recognize the word when they hear it, or be tested on spelling and proper usage of the word. As John Medina says in Brain Rules (a must read for any educator) “Deliberately re-expose yourself to the information if you want to retrieve it later. Deliberately re-expose yourself to the information more elaborately if you want the retrieval to be of higher quality.” (p.133)

There’s a lot more to say on the subject of repetition, including the importance of having some variety with each encounter and the timing of repetitions. I’ll write more about how Praxis does this in the next blog entry.

Sources

Anderson, J. P., & Jordan, A. M. (1928). Learning and retention of Latin words and phrases. Journal of Educational Psychology, 19, 485-496.

Crothers, E., & Suppes, P. (1967). Experiments in second-language learning. New York: Academic Press.

Folse, K. (2004). Vocabulary myths: Applying second language research to classroom teaching. University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor, MI

Folse, K. (2006). The effect of type of written exercise on L2 vocabulary retention. TESOL Quarterly, 40(2), p. 273-293.

Kachroo, J. N. (1962). Report on an investigation into the teaching of vocabulary in the first year of English. Bulletin of the Central Institute of English, 2, 67-72.

Nation, I. S. P. (2006). How large a vocabulary is needed for reading and listening? Canadian Modern Language Review, 63, 59–82.

Nation, I. S. P. (2014). How much input do you need to learn the most frequent 9,000 words? Reading in a Foreign Language, 26(2). 1–16

Seibert, L. C. (1927). An experiment in learning French vocabulary. Journal of Educational Psychology, 18, 294-309.

Seibert, L. C. (1930). An experiment on the relative efficiency of studying French vocabulary in associated pairs versus studying French vocabulary in context. Journal of Educational Psychology, 21, 297-314.