It’s a fact that languages are in a constant state of change and there isn’t much we can do about it. Though it is common to hear people bemoan the current state of English, I agree with linguists who argue that English is in no danger of being ‘corrupted,’ and indeed never has been. Throughout history, self-proclaimed defenders of the English language have warned that the language was on the precipice of collapse. Here’s an interesting article on a list of things that at different points in history people of the time feared would destroy the language. Most are just too silly to consider now (Shakespeare and the printing press were threats to the language?), just as 200 years from now native speakers will probably have a good chuckle at the current breed of so-called language experts (Stephen Pinker in The Language Instinct labels them ‘language mavens’) who warn that the Internet is destroying the language. A language can never become better or worse. It just becomes different as it adapts to serve the needs of those who use it.

Ol’ Slick Willie, plotting the downfall of the English language

Changes in grammar tend to be slow. Whom as the object pronoun form of who has been slipping away over the past century or two, at least in America (though I suspect it will survive in expressions that require it to follow a preposition, such as ‘most of whom’ and ‘To whom it may concern’). Another apparently ongoing change is in the unreal conditional use of ‘be’¹: ‘I wish I were good at grammar’ vs. ‘I wish I was good at grammar.’ I don’t recall any of the ESL/EFL grammar textbooks I used back in the mid-nineties even acknowledging the existence of the latter, but these days it seems most of the major grammar texts in the ESL/EFL market point out that was occurs in informal speech. In a hundred years or so, perhaps we’ll see the form change completely.

But while changes in grammar typically take decades if not centuries, changes in vocabulary occur far more rapidly. Every year thousands of slang words are created while an equivalent number blink out of existence nearly as quickly as they were created. Every new printed edition of dictionaries officially accepts hundreds of new words into the lexicon, while quietly deleting hundreds of outdated words to make room (the 12th edition OED added 400 new words while removing 200). Online dictionaries are not burdened with such space issues, and thus can add hundreds of new words each year (the online OED adds about 1000 per year) without deleting any.

Some of these changes are generally welcomed by most people, as the words fill a new gap that existing words cannot fill. As we are meeting and interacting with so many people online, people now have the need to distinguish ‘online’ and ‘offline’ relationships, classes, and so on (I recently read someone referring to the offline world as ‘meatspace’ as opposed to ‘cyberspace’. I really hope that term takes hold.). ‘Nomophobia’ is, I am told, the term for cell phone separation anxiety: the fear of being without your cell phone for even a brief period of time. Will it take? As I type this, I realize that my cell phone battery has died, and I can’t stop worrying that someone might be trying to contact me. So yeah, it just might.

Those of us on the older side of 40 might bristle a bit every time society foists yet another new word onto our brains that are already at maximum memory capacity. However, most slang has the life span of a fruit fly (we’re looking at you, ‘chillax’) and for the slang words that stick, despite our initial grumbling, the transition as a whole is relatively painless. Before you know it, we’re using words like humblebrag and mansplaining in a sentence without a second thought, if you aren’t already.

Outdated words usually fade from the lexicon without much of a fuss at all. Few people lament that words like gumption are now only found in old texts and SAT vocabulary lists. Personally, I just can’t use the word gumption with a straight face. It takes gumption to use a word like gumption to anyone other than your grandparents and expect to be taken seriously.

So sure, language changes and it’s not a bad thing on the whole. All the rantings from the language mavens who warn that English is going to hell in a hand basket are just tales told by idiots, full of sound and fury, signifying whatevs.

And yet…

Some apparent changes are just harder to accept lying² down. The following are changes in the English language that still bring out the language mini-maven in me.

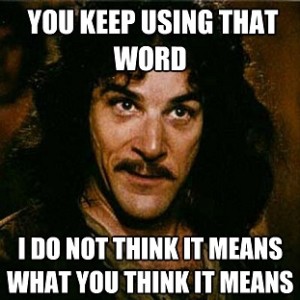

Literally used to mean the opposite of what the word was specifically created to mean.

I don’t literally pull my hair out when I hear people misuse this word (genes passed down from my maternal grandfather are already taking care of that for me), but I do literally want to verify that these people did not purchase their most recent diploma online for $19.99. Yes, I know that there are many words in the English language that have completely reversed their meaning and the world somehow keeps turning. Yes, I know that from context we can usually tell if a person literally means literally or not. I don’t care. These people simply sound dumb.

Mockery is the only way to reverse this tide. Each time someone says something like they ‘literally peed their pants’ out of fear, ask directly (and loudly) how they specifically dealt with their urine-soaked jeans. “What? You literally peed your pants? Did you go directly home to change said pants? Do you have a history of bladder problems? Do you wet your bed every time you have a nightmare? Have you considered therapy?” Keep asking annoying and embarrassing questions like these until the sinner finally breaks down and says, “OK, I didn’t ‘literally’ pee my pants! Will you shut up now?” They’ll think twice before misusing the word again. This is how we fight, people.

Ironic to mean anything weird, funny, or kind of screwed up

Isn’t it ironic that the Alanis Morissette song titled ‘Ironic” is completely lacking in examples of irony? Or is that the irony that Alanis intended all along?

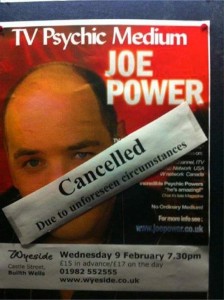

Fun Quiz! Which picture actually shows irony?Turn to the back of the Internet to see the answer.

Irregardless

I don’t mind double negatives in slang and music (Ain’t no thing if you can’t get no satisfaction), but use of irregardless always gives a bad impression. ‘Regardless’ is just a bit too far removed from informal speech to allow misuse without the raising of eyebrows and hackles. I have no problem with ‘unirregardless,’ though. The math checks out.

Beg the question vs. Raise the question

It seems that even many educated people do not know the meaning of begging the question. Begging the question is using circular reasoning. That’s a bad thing. Raising a question means bringing up a question. It’s usually a good thing.³

Could care less (?)

There are some misused expressions that are probably too late to save and we need to learn to be unbothered about. I was initially going to add could care less to the list, but after reading up on the controversy, I’ve been swayed. In the Language Instinct, Stephen Pinker defends this expression by saying the ‘I could care less’ form is used sarcastically. I doubt this. Every time I’ve heard someone use this, the speaker did not give off any vibe of sarcasm. It’s just an expression that was used carelessly by enough people for a long enough time until it stuck. It’s probably passed into the realm of the idiomatic, which is no longer ruled by logic (shouldn’t it be forth and back rather than back and forth? HOW CAN YOU COME BACK BEFORE YOU GO FORTH?!). What I guess I’m saying is that I could care more about people who say they could care less, but I don’t.

Footnotes

1. Also known as the past subjunctive to teachers and scholars who enjoy using language in public no one else understands nor cares about.

2. Please note that I didn’t write laying down. Here’s a sentence that can help you distinguish between lay down and lie down: “When too many people lay down word turds all over my Internet, I need to turn off my computer and lie down for a while.”

3. Of course, there are times when a question is not a good thing. I’ve broken it down here:

- The question is seriously stupid. We can’t define this for you; we just know a dumb question when we hear it.

- A student is asking questions in class solely for the purpose of getting the teacher off track (and damn it if it doesn’t work on me every time).

- The teacher asks you a question in class even though it’s clear to everyone in the room that you couldn’t possibly know the answer because you weren’t even pretending to pay any attention in the first place.

- You ask a perfectly reasonable question to a police officer who feels profoundly threatened by anyone he fears might be questioning his authority. Regardless of the question, the answer is usually, ‘Because taser.’

- Your spouse asks why you didn’t do something that you totally forgot to do, again, and you’re really tired of hearing that question because she already knows the answer anyway and of course eventually you’ll remember to do it, but you’ve just been busy with a lot of stuff lately and besides it’s not like she always does everything she’s supposed to do so why does she always have to nag about it? [edited for length]

Come to think of it, perhaps the good vs. bad question ratio is basically a 50/50 split.